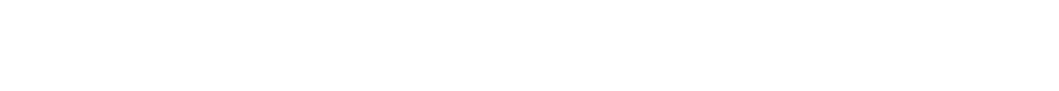

Incidents of GPS spoofing and jamming in or near conflict zones and other areas are on the rise and spoofing can be much more dangerous for civil aircraft operations than jamming.

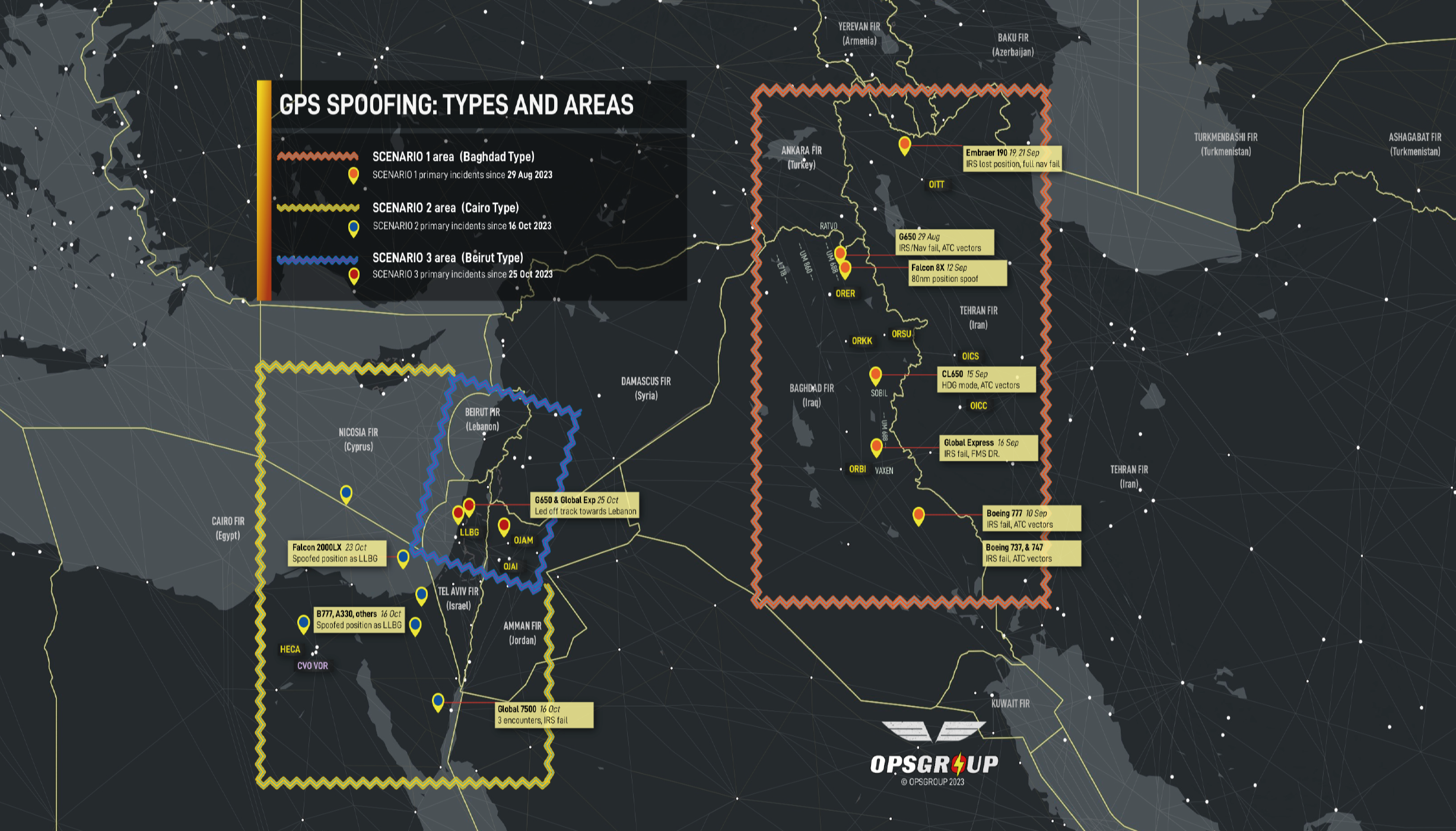

Reports of GPS spoofing and jamming started in the Middle East, spread to the Black Sea region, then Eastern / Northern Europe including Finland. They are now being reported near airports in Seoul and Beijing as well as Myanmar and sporadic encounters in central Asia.

GPS spoofing can cause receivers to fail, resulting in degraded navigation capability. Since many aircraft systems receive their information from these receivers, additional failures of other critical systems such as the GPS Clock, Weather Radar, ADS-B, Terrain Warning Systems and others may follow. Getting a terrain warning flying at 40,000ft can be disconcerting, to say the least.

The flight management computer (FMC) can also receive erroneous data from the GPS, so it may display incorrect and confusing information to the pilots. Once the GPS system accepts a bogus update, it calculates an erroneous position. The GPS shares the incorrect position with the FMC that is guiding the aircraft by weighing inputs from multiple sensors.

Airlines like to use DME/DME to navigate when GPS is unreliable or out of service. However, DME/DME won’t work if the Flight Management System (FMS) or pilots can’t tune a DME.

The FMS automatically tunes a DME or VOR navaid finding a frequency in a lookup table referenced to latitude and longitude location. With spoofing in Europe, the FMS may attempt to tune a DME two European national borders away from the aircraft’s actual current position.

Receivers playing catchup

Civil aviation is particularly vulnerable because of its deep dependence on GPS, according to Todd, E Humphreys, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s Radionavigation Laboratory.

Humphreys believes the civil aviation community has an inadequate safety mindset on air navigation which is making the world less safe because of the consequences of a potential security crisis.

“GPS receivers that are aviation certified are single frequency, which means that civil aviation is 20 years behind the technology curve,” Humphreys says. “These should be multiple frequency receivers using multiple satellite constellations – or at least add Galileo and L-5.”

Humphreys monitors GNSS interference reports and receives incident information from pilots by email.

EASA issued a Safety Information Bulletin No. 2022-02R2 in November 2023, which says GNSS interference incidents are growing in intensity, sophistication and severity of impact. Interference is difficult to detect and characterize and there are no specific flight crew alerts for it. The bulletin encourages mitigation measures for civil aviation authorities and ATM/ANS providers. The bulletin noted ATM/ANS providers should have ways to collect information and ways to monitor traffic closely to spot any flight track deviations.

An airline aircraft’s Inertial Navigation System (INS) can use positioning updates from DME/DME and DME/VOR fixes. But in one case when an airline aircraft headed back from Dubai to the USA and coasted out over the North Atlantic, it had to rely on INS alone. INS provides a positioning that drifts off one nautical mile per hour on average. The incident and the amount of drift that occurred over the ocean without GPS updates raised questions as to whether the aircraft could maintain the required navigation performance (RNP) accuracy.

ATC got confused and issued a lower altitude clearance for the aircraft, which then had to land short of its US destination to refuel. Not exactly an ideal way to navigate over the ocean.

This incident was described by Boeing 777 Captain and QCI check pilot Bulent Ince. He follows spoofing incidents and compares notes with leading avionics companies. Ince has more than 26,500 flying hours and just retired from a major US airline.

“I would rather be jammed than spoofed,” says Steve Fulton, an air navigation expert who is a captain with Alaska Airlines. “RNP [Required Navigation Performance] procedures in remote areas with significant terrain constraints are dependent on GPS for high levels of RNP,” Fulton said. “There are significant provisions for the aircraft to operate safely in the event of a loss of GPS. However, sophisticated GPS spoofing that introduces small but consequential position errors would be difficult for the aircraft system monitors to detect and isolate.”

Incident identification

Both GPS jamming and spoofing interfere with pilot situational awareness, according to Dana Goward, president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing (RNT) Foundation in Alexandria, Virginia. The RNT Foundation advocates for policies and systems to protect GPS users, including terrestrial backups.

“GPS jamming results in no information, while spoofing results in hazardously misleading information,” says Goward. A pilot can spot the problem by maintaining situational awareness, dead reckoning and using all means available to determine the aircraft’s actual position. “Often this is the only way to recognize you are not where the GPS says you are,” he adds.

In the US Coast Guard Goward flew as a rescue helicopter pilot and later managed the service’s US$1.3 billion per year navigation programme.

Goward says he isn’t sure air traffic controllers can always spot GPS interference: “Clearly if an aircraft is suddenly far from where it should be and the track looks really strange, then spotting it should be pretty easy.”

More events with subtle spoofing of GNSS are happening now. One airline aircraft in Turkey was almost lured into nearby Iranian airspace, where the intrusion could have been a fatal error. Another indicator of GPS interference is if the ADS-B feed is lost.

In an emailed response, the FAA said that it is “working with civil aviation authorities to address spoofing and jamming by sharing information and issuing NOTAMS to inform pilots about potential disruptions”.

The FAA reports that it has not issued any NOTAMS for GPS spoofing in the US. The agency did issue a GPS jamming and safety alert for civil aircraft operators flying globally on January 25, calling for pilots to report any such anomalies to ATC.

The FAA alert lists possible impacts on cockpit systems and calls for pilots to revert to using conventional navaids. The FAA says it is working with interagency and international partners on ways to identify and mitigate spoofing. GPS interference have been detected on the US border with Mexico, but this may involve the US Government countering drone incursions, according to one industry insider.

The USA’s National Airspace System does have backup terrestrial systems including VOR, DME AND ILS. The FAA has decommissioned 174 VORs but plans to retain 593 in the continental U.S. The agency is also assessing potential options for decommissioning a limited number of Category 1 ILS systems. Goward thinks the current plans to downsize ground-based navaid coverage may be going too far.

The FAA also says a NextGen DME programme will expand coverage for area navigation (RNAV) in high altitude en route airspace and at the busiest airports in the USA. The FAA will fill coverage gaps with 129 new DMEs, 15 of which are already in place. Aircraft can fly DME/ RNAV if GNSS/RNAV is not possible to join an ILS approach. Once all the new DMEs are installed, the FAA may decommission some that are not used with conventional VOR/ILS procedures. Multi-scanning DME receivers on airline aircraft can achieve RNAV-1 requirements. The FAA is working on standards for DME/RNAV operations.

AOPA says it sees GPS spoofing becoming “a big deal, especially overseas”. If it spreads to the USA it will become an issue for AOPA members. Humphreys believes GPS spoofing will occur in the USA eventually. All sectors of the US economy that depend on GPS are vulnerable to cyber-attacks. The RNT Foundation is advocated for protecting all sectors not just aviation.

Defensive measures

The military has ways to defeat GPS jamming and spoofing in aviation it is not sharing with civil aviation. Brad Parkinson, the man credited with driving the development of GPS, laments the lack of GPS anti-jamming technology aboard civil aircraft. When GPS was originally developed 50 years ago, he conducted anti-jamming demonstrations with then Rockwell Collins (now Collins Aerospace) in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Parkinson notes that multiple-element antennas can defeat strong GPS jammers and spoofing for civil aircraft. However, International Traffic in Arms Regulation (ITAR) won’t allow these antennas to be installed on US civil aircraft or ships.

Meanwhile, civil manufacturer Tualcom Electronik in Ankara, Turkey is making eight and 16 element GNSS anti-jam antennas which Parkinson suspects are being used on the Iranian drones employed in the Ukraine war. If the technology is available to people outside of the USA, the ITAR restrictions are redundant. Indeed the U.S. National Positioning, Navigation and Timing Advisory Board of technical experts has been pleading with the US Government to drop the ITAR antenna restriction for several years.

“The spoofing we are seeing in Europe is being caused by state actors, in particular Russia,” says Humphreys. “However, it is possible for an individual to carry out a spoofing attack. Anyone can download the software put it on a $300 off-the-shelf radio, hook it up to an amplifier and be in business.”

Rising levels

The USA has had some significant GPS incidents. A 2024 report prepared by the analytics firm London Economics studied GPS disruptions at Denver International Airport (DEN) and Dallas Fort Worth International Airport (DFW) in 2022, funded by the RNT Foundation. The report found that at Denver an accidental transmission from a government installation on January 2, 2022, impacted aircraft within 50 nautical miles of the airport for 33 hours before the source was identified and turned off.

On October 17 the same year at Dallas, the GPS interference source was not identified but it affected aircraft within 110 nautical miles for a day. Pilots near Denver filed 19 reports on GPS problems to NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System and 28 other reports were filed from flights over Colorado. No effect on traffic was observed at either airport as pilots switched from GPS procedures to ILS, VOR and DME.

EUROCONTROL notes that GNSS radio frequency interference puts a higher workload on pilots and air traffic controllers and a premium on backup systems including navaids. The European ATM body has been following voluntary pilot reports of GNSS outages since 2014 and, as of 2023, data from automated monitoring observing ADS-B transmissions. The agency shares information with airlines to increase pilot awareness and for route selection. It also shares the information with EASA, ICAO and IATA.

EUROCONTROL monitoring shows that GPS degradations of flights rose from 2.41% in the first week of 2024 (2,776 out of 115,037 flights) to 3.34% in the third week of March (4,387 out of 132,189 flights). In comparison, the first week of last year registered at lower levels of 1.75% of flights with GPS degradation while the third week of March registered 2.08%.

“It can be very difficult to determine if the degradation is by jamming or spoofing,” says EUROCONTROL.

There is no evidence of deliberate attacks on aviation which may be collateral damage in these interference events.

Humphreys thinks the civil aviation industry will be dealing with GPS spoofing for a long time.

A new resolution on the special protection of GNSS frequency bands passed at the ITU’s World Radiocommunication Conference in Dubai in December 2023 calls for preventing harmful interference to GNSS frequencies. However, a phrase stipulates this is “without prejudice to the right of administrations to deny access to GNSS for security or defense purposes.”

In other words, any nation can interfere with these frequencies within their borders for “security and defense purposes.” Humphreys believes this could be for almost any reason.